The Problem With Immigration Isn’t Immigration

Immigration, fear, and the quiet cookie thief who keeps America divided.

Black Hawk helicopters over Chicago. Children standing barefoot in the street, wrists zip-tied, still in their underwear. It is easy to think what we are seeing is chaos, a system breaking down.

But what if it isn’t? What if this is the system, doing exactly what it was built to do?

In this essay, I trace how America’s immigration crisis became less about borders and more about power, a story of how fear, profit, and policy turned human beings into leverage. It is a story about the man behind the mountain of cookies, the quiet theft that keeps us divided and fighting over crumbs.

Because the problem is not immigration. The problem is the economy we built on fear. And the invitation, for immigrants and citizens alike, is to remember what it means to stay human in a system that keeps trying to make us forget.

Watch or Listen

The Whole Story

I opened Instagram and saw the footage unfold. Black Hawk helicopters hover low, splashing into a Chicago neighborhood. ICE agents flood the streets. Children, ripped from their beds now standing on asphalt, some in nothing more than their underwear. Trembling hands are bound by zip ties. My heart tightens as my gut painfully whispers, How did we get here?

How Did We Get Here?

The question is especially poignant when, at least in our national ethos, we declare:

Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

But now, the very people who were once invited are universally deemed hardened criminals, less than human invaders who must not only be rounded up and cast out, but humiliated along the way. And if, in the process, we happen to get some documented immigrants or native born sons and daughters, that’s just the price of our supposed liberty.

Now the truth is, there’s always been a level of immigrant blame in this land of immigrants. Once it was the Irish. Then the Chinese. Then the Italians. Then the Mexicans. Now it’s Venezuela’s turn. Which should make us stop and think about what’s happening below the surface, a system that, on one hand, both invites and depends on outcasts from other parts of the world, those longing for opportunity, but simultaneously rejects them once they arrive.

And maybe the best place to start the exploration of that system is, well, cookies.

Immigration and Cookies

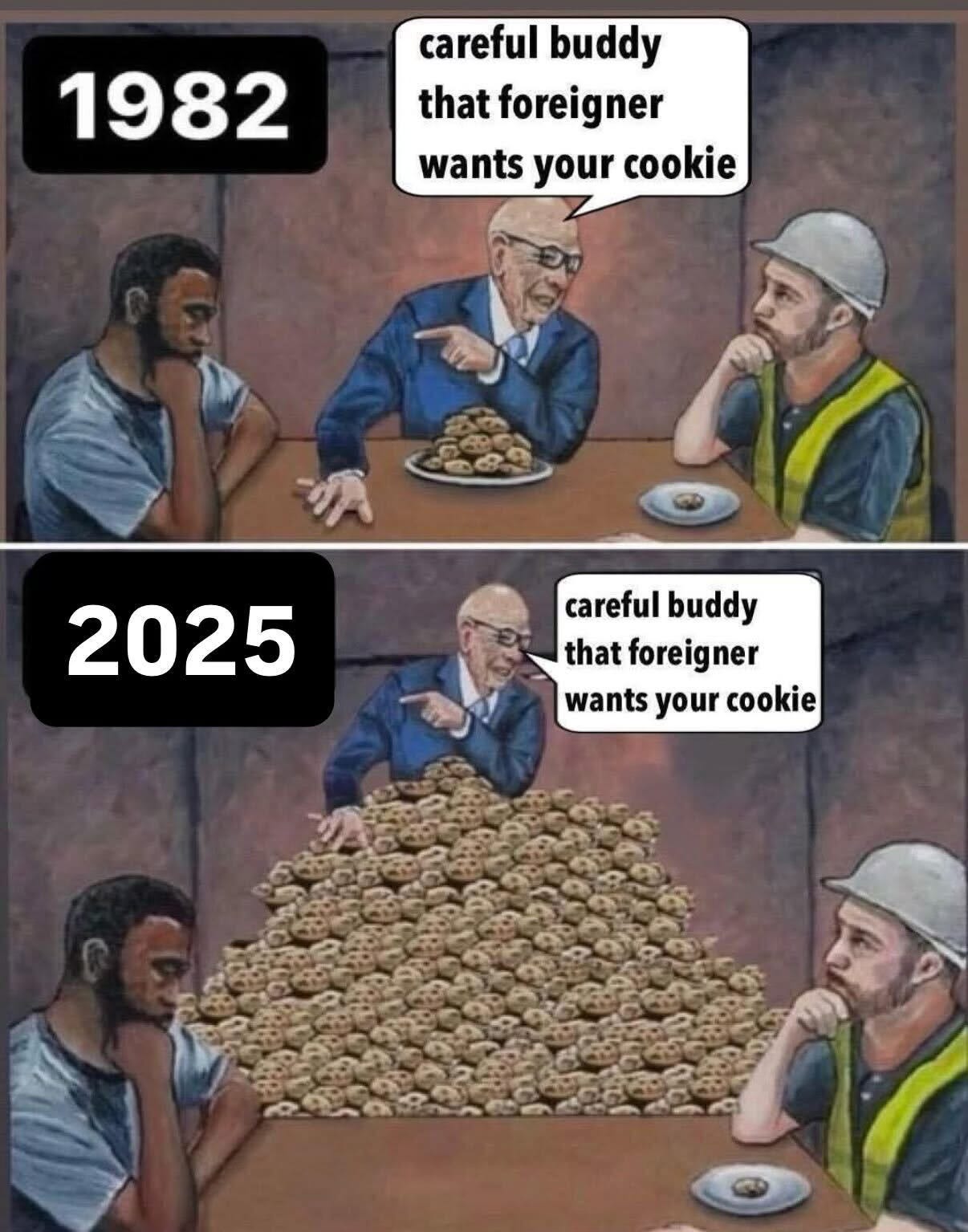

That might sound strange but on that same Instagram feed where I saw Blackhawk helicopters I also saw a familiar but updated meme. I’d seen the top half a few years back, but it was now labeled “1982.” It featured three men sitting at a table. On the right was a white guy in a hard hat. On the left, a person of color looking rather disheveled. Between them, an older white guy in a business suit. On the table before them, the guy with the hard hat had a plate with a single cookie. Before the person of color, nothing. In front of the businessman, a plate full of cookies.

As they’re sitting there, the business man leans towards the guy in a hard hat, points at the foreigner and says, “Careful, buddy, that foreigner wants your cookie.”

In the bottom half, labeled 2025, everything is the same except the business man is now peering up from behind a mountain of cookies. Same lie, bigger pile. And I thought, that’s it. That’s the story of immigration in America. A story about who we fear, who we blame, and who keeps hoarding all the cookies while encouraging everyone else to fight each other over crumbs.

Immigration in the Reagan Era

Consider the story of immigrants in American just during my lifetime. I grew up in the 1980s. Reagan was the president. We were told America was shining again, that the economy was roaring, that freedom had won. And while there was a national conversation about immigration, I was largely oblivious.

Later I learned that while I was riding my bike around the block and watching Saturday morning cartoons, the president was signing the last great amnesty in American history. Three million people, mostly from Mexico and Central America, were given legal status. The law was called the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. It was supposed to solve everything. We would legalize those already here, secure the border, and fine companies that hired undocumented workers.

But what I didn’t know then, and what most of America still doesn’t want to face, is that the tension around immigration was never simply about jobs or borders. It was about power. Politicians were caught between constituents demanding border control and industries demanding cheap labor. So they built a system meant to please both. A wall for the cameras. A wink for the corporations. Enough enforcement to win votes, enough loopholes to keep the economy humming. The result was a structure that kept immigrant labor visible enough to be blamed, but invisible enough to be used. We legalized people, but not dignity. We fixed paperwork, but not the power imbalance.

Invisible People

I did not see any of this when it was happening. The whole thing passed right through my childhood like a ghost. And I think that is part of the story. In my world, everyone looked like me. The grocery store clerks, the teachers, the neighbors, even the janitors at school. I am sure there were immigrants nearby, but I did not see them. Or maybe I saw them and didn’t know what I was seeing. At some level I knew they must be there, if nothing else because Colorado passed a law during my middle school years that required Spanish language inclusion on public documents and someone must have needed Spanish text, but that is how invisibility works. It hides in plain sight.

As I arrived in Seward, Nebraska, for undergrad I started hearing whispers. Stories about Mexicans in meatpacking plants. About small towns nearby where the church marquees were in English but the grocery shelves in Spanish.

I left Nebraska to be a youth pastor in northern California. There, in the middle of Sonoma County vineyards, I was embarrassingly oblivious to the immigrant world around me. Our congregation was mostly white suburban families, and I rarely saw the Mexican laborers who picked the grapes that became the wine served at our communion tables and dinner parties. They were invisible to me. Except for the moments at the post office, where I’d see a few men in dusty work clothes sending money home. Then they’d disappear again, back into the fields, back into invisibility.

Even today, I do not often encounter immigrants in my everyday spaces, although I do encounter the fruit of their work. Sometimes that fruit is the literal fruit and other produce I buy at the grocery store. The same most likely holds true for the butchered meat. Odds are high the home I live in was built by laborers from across the border. And anytime I buy something that’s moved through a warehouse, odds are good, it passed through at least one immigrants hands.

The one place I used to always be able to count on an interaction, the parking payment booth at Denver International Airport, which always seemed to be staffed by an Ethiopian, is now automated. We’ve made invisibility efficient and tucked exploitation into the shadows.

Jobs Americans Won’t Do

We like to say there are jobs Americans just won’t do. The truth is simpler and uglier. These are jobs Americans once did until they stopped paying enough to live on. When wages fell, protections vanished, and dignity disappeared, so did the native-born workforce.

In the early 2010s, when states like Alabama and Georgia passed anti-immigration laws, thousands of farmworkers vanished overnight. Farmers raised wages from seven to fifteen dollars an hour to lure citizens into the fields. They came, for a moment. But the work was backbreaking, the pay unstable, and the conditions punishing. Within weeks, most had quit. Not because they were lazy, but because the jobs were designed to break people.

The same story runs through meatpacking. Once union jobs that could support a family, those plants became low-wage and dangerous after companies busted unions and moved operations to rural towns where immigrant labor could be controlled. When immigration raids occasionally thinned the workforce, wages went up and locals came back … until corporations reopened the border of exploitation.

Immigrants didn’t steal those jobs. They filled the vacuum left when the system decided exploitation was cheaper than fairness. We built an economy that depends on invisible labor and then call that invisibility a choice.

From Invisibility to Theatre

Well, at least until we find ourselves back in that meme, hard hat on, looking down at the plate before us. We think of all the work we’ve done, and wonder how we only have a cookie to show for it. And in that moment, the one where we feel vulnerable and exhausted, the only voice speaking to our pain is the man telling us that the problem is the person with no cookie at all.

That voice from behind the pile of cookies encourages us to envy those above us on the economic ladder, believing that if we work hard enough we can be just like them, but simultaneously fear those below us, certain they are there to kick the ladder out from under us just before we make it to the top. So we keep hustling and guarding what little we have instead of asking why so little is left to share. All as the businessman’s pile of cookies grows taller. Eventually, something snaps and some of those in hard hats, lash out. Not because they’re racist or hateful, but because they’re trying to defend their own from a perceived attack.

That’s how we go from immigrant invisibility to the theater of Black Hawk helicopters. And there’s the deeper irony. When immigrant labor serves our needs, it must stay unseen. But when immigrant bodies work as a scapegoat, they must be paraded. Invisibility by day, spectacle by night.

The Scarcity Story

It’s all part of a story we’ve been told for generations. It says there are only so many chairs at the table. So when an immigrant sits down, someone else must stand. It sounds reasonable. It sounds like math. But it’s really mythology disguised as economics. Researchers have studied this question for decades. Do immigrants take jobs from native-born workers? The answer: sometimes, in small pockets, for a little while.

When new workers arrive in a small town or a single industry, especially when wages are low and mobility is limited, there can be short-term strain. A few people may lose hours. A few wages may dip. The same kind of pain that ripples through any economic change. But when you zoom out and look at the whole picture, the data tells another story.

Immigrants and the Economy

Immigrants don’t shrink the economy. They expand it. They build the houses. They clean the hospitals. They drive the trucks and pack the meat and code the software. And then they buy groceries, and pay rent, and need shoes for their children. Their work and their lives ripple outward. They do not take slices from a fixed pie. They make the pie bigger for everyone sitting at the table. Economists call this complementarity. It means the work of one person makes the work of another more valuable.

A new farmhand means more produce to transport, which means more jobs for truckers and warehouse crews. A new home health aide means more freedom for a family member to take another job. A skilled immigrant engineer means more innovation, which means more demand for local contractors and suppliers.

The studies are surprisingly consistent. On average, immigration increases wages slightly for native-born workers. In most regions, more immigrants mean more jobs, not fewer. For every twenty immigrants employed, another job opens for a citizen.

Immigrants and Social Services

Some argue immigrants drain the system, taking more in benefits than they contribute. The numbers tell another story. Year after year, immigrants pay far more into the economy than they receive. In 2022, undocumented immigrants alone paid nearly one hundred billion dollars in federal, state, and local taxes. That’s money that supports schools, hospitals, and infrastructure most will never directly benefit from. Many also pay into Social Security and Medicare, programs they are legally barred from accessing. The truth is, they help fund the very safety nets that too many Americans believe they are burdening.

Corporations vs. Immigrants

But what about that businessman behind the pile of cookies? While immigrants file their taxes through whatever means they can, often using tax identification numbers or borrowed Social Security numbers just to participate in the system, many of our largest corporations treat taxation like an optional courtesy. Walmart alone sidesteps an estimated one billion dollars in U.S. taxes annually through carefully constructed loopholes. The public, meanwhile, absorbs billions in costs tied to their poverty-wage workforce, as I previously explored. In 2020, more than fifty profitable corporations reported zero federal income tax despite raking in billions. They take from the commons while contributing nothing back. When we’re told immigrants “drain the system,” we’re being sold a lie designed to keep us from seeing where the real hemorrhaging occurs. It’s the same misdirection: “Careful, that foreigner wants your cookie,” whispered by the man actively eating the whole pile.

The H1-B Visa Debate

Even in the world of so-called legal immigration, the system bends toward the same power. Consider the H-1B visa, a golden thread that looks like opportunity but functions more like a leash. Created for skilled workers, engineers, developers, scientists, researchers, it appears on paper to be a bridge between need and talent. In practice, it has become a mechanism of control, a way to tether a person’s dreams to their employer’s whims.

These corporations bring in brilliant minds from across oceans, not always because talent is absent here, but because a visa-bound worker carries a different kind of vulnerability. Their right to remain depends entirely on their employer’s grace. Lose the job, lose the visa, lose the life you built. That precarity creates compliance. A worker who knows deportation is one termination away becomes a worker who doesn’t organize, doesn’t question, doesn’t leave for better conditions. The visa doesn’t just bring talent. It manufactures silence.

Meanwhile, in the work that truly sustains life, nursing, teaching, caring for elders and children, our immigration system builds walls where it should be building bridges. We’ve engineered a system that makes it easier to import engineers for Silicon Valley than nurses for our hospitals, easier to staff corporate tech campuses than to fill our classrooms with teachers. The gate stays wide for those who serve capital and narrow for those who serve the body and soul. This is not accidental. This is the system announcing its values, declaring that profit matters more than care, that shareholder returns outweigh the dignity of the elderly, the education of children, the health of communities. The system rewards extraction and punishes tenderness.

So once again, the circle repeats. Those at the top extract profit from both scarcity and control, while everyone else, immigrant and citizen alike, is left to fight over what remains.

Natives Taking Immigrant Jobs

And in what might be the biggest irony of all, in many situations, you have native born Americans are trying to take jobs from immigrants. We see this in the rust belt and old mining towns. These are the places where blue collar Americans used to have jobs right where they were. But those jobs are no longer there. They’ve been exported and off-shored because the same people who publicly told us to fear immigrants were busy behind the scenes advocating for trade deals that rewarded the shareholder. So the jobs that native-born workers once held weren’t stolen by people crossing the border. They were sold by people crossing oceans in private jets. Immigrants didn’t take the factory. The factory was dismantled and exported for profit.

When the factories left, the jobs that stayed behind were the ones we had given to immigrants for decades. The work that could not be shipped: the harvesting, the cleaning, the caring, the building. The work that stays close to the human body. So when these hard working Americans looked around after the mills closed and the machines fell silent, all they saw were immigrants still working. They thought the immigrants had taken what was theirs, when in truth they had simply remained where the economy had always needed their hands.

So when fear rises, it rises where pain already lives. And the voice from behind the pile of cookies knows exactly what to say. He points to the now unemployed factory worker and whispers, “See, that’s who took your job.” He never points to himself. He never mentions that the system that squeezes you is the same system that exploits them. He never confesses that both of you are working harder for less. This is the hidden truth behind the illusion of displacement. Immigrants are not the threat. They are the mirror. They show us how deeply our nation depends on invisible labor. They reveal the fragility of an economy that demands cheapness from the masses so that few can feel secure. And until we can see them, really see them, we will never understand what is happening to us.

This is the real story of immigration in America. It is a system that creates dependency at the bottom and immunity at the top. Until we confront that reality, it will keep turning human beings into leverage, one visa, one border, and one policy at a time.

Where Do We Go From Here?

So what do we do about immigration? How do we all, native and immigrants alike, stay human in a system that depends on cheap and controllable labor, while simultaneously blaming the very people we depend on for all of our national problems?

Choosing Love Over Fear

Maybe it all starts by admitting that what we call an economic crisis is really a spiritual one. Because at its root, the story that drives our economy is not about numbers or markets. It’s about fear.

We have been trained to believe there is not enough. Not enough jobs. Not enough homes. Not enough safety. Not enough love. So we clutch, compete, and guard. We build policies the same way we build walls, trying to keep what we think is ours. And every time we do, we grow a little less human.

The Hebrew Scriptures say, You shall not oppress the foreigner, for you yourselves were foreigners in Egypt. The Qur’an reminds us that God created us into nations and tribes so that we might come to know one another. And Jesus told a story about a kingdom where the invited guests refused to come, so the host threw open the doors to the streets and filled the table with strangers.

Every tradition worth its salt tells the same truth: that our humanity expands when our circle does. Scarcity is not the story of the universe. It is the story of empire. And empire survives by keeping people afraid. So if the man behind the pile of cookies has a religion, that’s it. Scarcity. Fear. Division.

But love has its own economy. Love multiplies the chairs. Love trusts that the table can always grow.

So what does it mean to stay human in the middle of this machine?

From Division to Solidarity

It starts by seeing the exploitation that exists throughout the system, the abuse of native born and immigrants alike. We organize across lines meant to divide us. That means citizens and immigrants, white and brown, rural and urban. Because our future depends on our togetherness more than our separateness.

But solidarity is not simple. It asks us to see what history has made hard to face. For those of us who are white and native born, especially white and male, it means reckoning with the ways we have been trained to see Black, brown, and female bodies as competitors or threats. We were handed a lie that our worth depended on staying above someone else. For those who are Black, brown, Indigenous, female, or queer, it means living with the truth that this lie has caused real suffering. Generations of it. Those wounds cannot be ignored or wished away. To move forward together, both must happen at once. The privileged must take responsibility for what their comfort has cost. The wounded must be honored in their pain without being asked to forget it. Solidarity is not pretending the past did not happen. It is choosing to build a future that makes sure it does not happen again.

Then, together, we have to face the man behind the pile of cookies. Because the truth is, he is not just hoarding them. He is taking them. While we argue over crumbs, his corporations keep posting record profits. While we are told to fear migrants and resent the poor, his lobbyists rewrite the laws that let him keep the pile growing. He funds both sides of the argument, the candidate promising to build the wall and the one promising to keep the market open, because both keep him in control. Every time we turn against each other, he gets richer. Every time we organize together, he gets nervous.

That is why solidarity matters. It is not a sentimental idea. It is the only force that threatens the pile. When native-born and immigrant workers stand side by side demanding living wages and fair treatment, they begin to reclaim what was stolen from both of them. When teachers, nurses, and builders see their struggles as one, the whole story begins to change.

Solidarity is the act of turning toward each other instead of turning on each other. It is looking across the table and realizing that the person we were told to fear is the same person we must link arms with if we are ever going to be free. Because the problem was never the man with no cookie. The problem is the one who keeps taking them all while convincing the rest of us that this is just how the world works.

Examples of Solidarity

There are already stories breaking through the noise. Meatpacking workers, both documented and undocumented, striking side by side for safe conditions. Day labor centers offering free meals and English classes for anyone who walks through the door. Churches turning their fellowship halls into sanctuaries, not out of pity, but out of conviction that every person belongs.

The opposite of exploitation is not charity. It is solidarity. It is the recognition that my liberation is bound up with yours. That the only way to protect what we have is to stop hoarding and start sharing. When we do that, the walls that separate “us” and “them” begin to crumble. And in their place, we find something that looks a lot like home.

Back to Helicopters

I keep thinking back to that night, the helicopters circling over Chicago, floodlights cutting through the dark. I remember how my heart ached and whispered, How did we get here?

Maybe the more important question is, How do we get back? Not to some mythical past of national greatness, but to the deeper knowing that our lives belong to each other. Back to the lamp beside the golden door, not as a slogan, but as a way of life. Back to the truth that the land we stand on was never meant to be owned, only tended.

The work ahead is not to fix immigration. It is to restore our humanity. To remember that the people we are taught to fear are the same people who can teach us how to love again. When we stop mistaking fear for wisdom and control for safety, we begin to heal. And when we lift the lamp again, even with trembling hands, we discover it still burns bright.

Because underneath all the policy and profit and propaganda, the human story remains the same:

We were made to belong.

We were made to share the table.

We were made to stay human.

Practices For Solidarity

This week I am offering three practices that will help you step into solidarity. Whether your day only allows for a 60-second reclamation reflection, your week a one-hour resistance ritual, or you find yourself ready for a full on rebellion against a world that assaults your humanity, I have something for you.